Surf China’s Censored Web at an Internet Cafe in New York

By Claire Voon

Surf China’s Censored Web at an Internet Cafe in New York

It may have been a while since you’ve set foot in an internet cafe, but a pop-up one on the Lower East Side offering free tea on top of free wifi is well worth a visit for a lesson in online freedoms. Established by video and installation artist Joyce Yu-Jean Lee in collaboration with technologist Dan Phiffer, the exhibition FIREWALL Internet Cafe NYC at Chinatown Soup enables visitors to navigate the internet as users in China do, filtered through the Great Firewall — from which the show takes its name. It allows you to experience, firsthand, the effects of internet censorship by the Chinese government that frustrates so many on a daily basis, and understand how different levels of accessibility may shape our understanding of our surroundings.

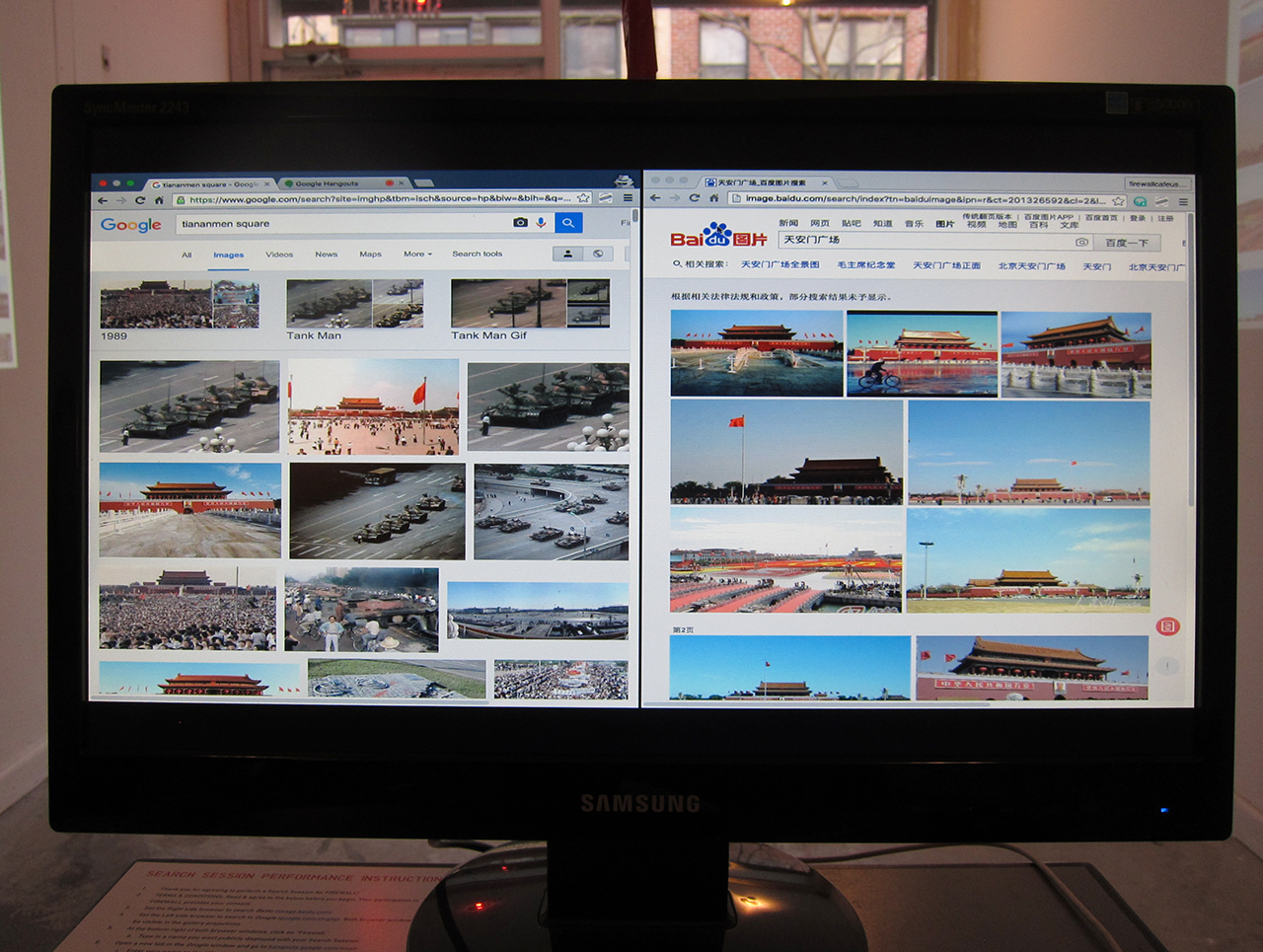

Each of the seven computer stations available is set up to display a split-screen of Google and Baidu (China’s leading search engine) so you may simultaneously surf the web in the US and in China. You may enter anything you wish into either search bar — depending on your language skills — and Lee and Phiffer’s custom-coded plugin will run a side-by-side image search then display the results. They’re almost always different, although, as you may imagine, the disparity between results for a search like “tiananmen square” is greater than that for something like “peanut.” Sociopolitical matters are among the more heavily censored material; “tiananmen square,” as Lee said, has actually been one of the most popular searches in her cafe. When you input the terms and hit enter, Google pulls up the famous image of the “tank man,” among other photographs related to the June 4, 1989 massacre; Baidu, however, finds scenic snapshots of the city square. The browser also posts a line above the results that notifies users of the sensitivity of their search subject.

FIREWALL also makes you aware of the differences in internet accessibility within China itself. The results for the same search may vary as each computer is connected at any moment to one of a handful of remote IP addresses owned by the anonymous Chinese hacktivist group GreatFire that Lee contacted to assist with the project. Although implemented and owned by the Government of China, the Great Firewall varies in strength from city to city — censorship tends to be more lax in metropolitan centers popular with foreigners such as Shanghai — so “Ai Weiwei,” for example, may bring up different search results depending on the IP address used that day. You may also browse the searches previous FIREWALL Internet Cafe visitors have made online, where browsing activity is archived via Google Hangouts. The cafe also projects these recordings in its physical space, switching to real-time projections whenever someone uses the cafe’s main computer station, which is isolated front and center in the entrance room.

Searching for more abstract terms also yields strange results, some of which illustrate differences in culture. “Happiness,” on Google, pulled up stock images of sunsets featuring silhouettes of people leaping up into the air; Baidu, however, brought up photographs of heterosexual weddings and one-child family pictures. “Myself,” entered into Google’s search bar, brought up images of the pronoun rendered in garish type, while the Baidu translation resulted in a lot of selfies, posted originally on social network profiles. Lee described this instance as “reverse censorship,” exemplifying a form of censorship implemented in the West to protect identity, while safeguards against such leaking of private information have yet to be erected in China.

The differences in results are likely frustrating to users in China, who have to use VPNs to bypass government censorship. But just as tedious is the speed of network connections, which the computers in FIREWALL also illustrate. You can observe the slowness as the browsers at times simply freeze or the image search results take a long, long time to load, forming one by one rather than as a whole, instantaneous grid. The speed, Lee said, at times also depends on the search term and the topic’s level of sensitivity.

FIREWALL is seven thousand miles away from China, but the exhibition has received backlash from the Chinese government, including pressured to self-censor. On the night before one of the project’s panels, according to Lee, one of the speakers — a woman known for her vocal opposition of the single-child policy — received several threats from the government, resulting in her voluntary withdrawal from the discussion for safety reasons. Lee also decided to pull all Chinese nationals from the show’s future programming since many of them work with internet freedom organizations, and the Chinese government, she says, keeps tabs on their careers.

“I thought, as an artist, that I would show the presence of censorship online,” Lee said. “Never at any point in time did we think censorship would affect our programming in New York. It’s a wakeup call … especially knowing I’m probably on a government watchlist right now.”

To represent and honor all those unable to speak in their programs and whose safety is now threatened because of their connection to the exhibition, FIREWALL now includes a chair with red tape across its seat. The display originates from the incidents surrounding imprisoned dissident Liu Xiaobo, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010 but was unable to receive it. At the ceremony, an empty chair marked his absence; on the internet, the Chinese government had censored the term “empty chair.” Many people in China who had attempted to discuss the incident online found their posts deleted or their accounts blocked. Such a series of events exemplifies the importance of a show like FIREWALL, especially as discussions are underway over China’s impending Cybersecurity Law — which may require Internet providers to censor users and aid in government surveillance of citizens in the name of national defense.

“The show has been very educational for people coming in,” Lee said. “It’s a privilege we can talk so much, and so openly, about internet censorship here — because a lot of people can’t.”