Virtually Real. Conversations on TechNoBody – Part II

Virtually Real. Conversations on TechNoBody – Part II

In the Digital Art Series

This interview is a continuation of the discussion with curator Patricia Miranda and artists Claudia Hart, Carla Gannis, Victoria Vesna, Laura Splan, Cynthia Lin, Joyce Yu-Jean Lee, and Christopher Baker around the TechNoBody exhibition opened on January 23, 2015, at Pelham Art Center in New York which explores “the mediated world’s impact on the relationship to the physical body in an increasingly virtual world.” While the first part of the interview addressed the show’s nomenclature, the selection of works, the artists’ views on the idea of virtuality and various ideas related to culturally constructed meanings, pictorial spaces, virtual environments, the aesthetics of navigation, or corporate mannerisms – the discussions continue here by investigating gaming technologies and iconography, corporal faults, embodied knowledge, participative media, human-machine relations, cyber feminism, virtual communities, corporate marketing, avatars and data bodies.

Sabin Bors: Claudia, your latest body of works is focused on the use of software and gaming technologies filtered through feminist perspectives. It continues what I always appreciated about your work, namely the juxtaposition of several aesthetics corresponding to opposing ideologies. How do video games impact the aesthetics of contemporary art, in your opinion, and how can feminism subvert these technologies to propose refined, alternative perspectives?

Claudia Hart: I think that first-person-shooter games embody the qualities of the corporations that produce them. Several years back, the US Supreme Court endowed corporations with the constitutional rights of a human being. Organizations based on profit motive were put on par with the human! This blew my mind. Shooter-games treat human avatars as objects, objects to be consumed and annihilated.

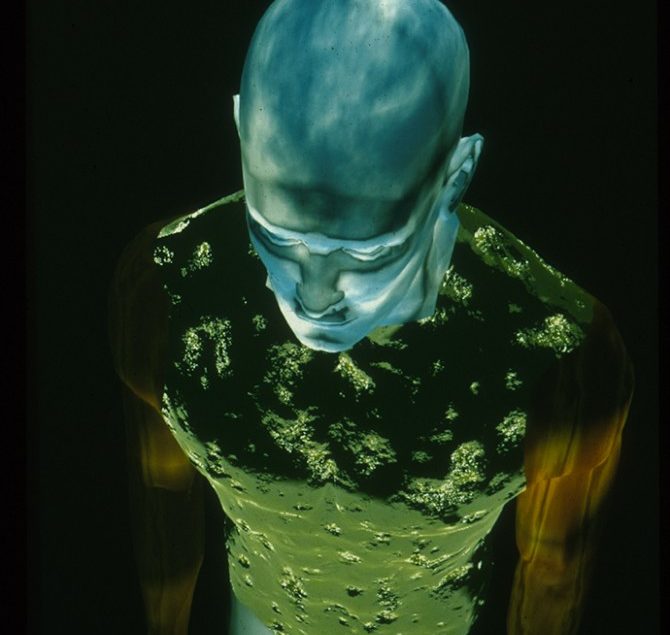

My idea of feminist practice is a deeply Humanistic one. I think of feminism as a form of resistance to the tendency of dominant culture to dehumanize others. In reaction, my representations are of very humanized avatars. I want them to express the pain of being and the vulnerability of the body; I want them to express their anxiety about dying within a virtualized artificial space. I’m not sure if my spaces are specifically game spaces, although game spaces are certainly a version of a virtual environment. In Patricia’s show, my work Dark kNight and On Synchronics – a related collective work done by 24 of my former students and I – both portray an avatar transmogrifying and being battered in a virtual world. I want viewers to feel its pain and also to be moved by its death. It’s my point of resistance to the dehumanization of corporatized media.

Sabin Bors: You create corporal landscapes that question a series of issues such as gender, identity, beauty, or mortality. Did you also build these corporal landscapes to subvert the conventions of the artistic nude, Cynthia? If so, in what way? What do our corporal faults tell about our bodies and the history of body representations?

Cynthia Lin: Really great observations! Traditionally, the nude was a female presented for the enjoyment of the male viewer. It was also the artist’s means of “possessing” the woman. I aspire to subvert or newly define what “enjoyment” can be, as well as to challenge the traditional gender roles. The hyper-detailed depiction could be seen as a means of “possessing” or owning the image… but it also hints at the question of who owns digital images. The sense of power or possession usually claimed by the artist/viewer might be given over to a sense of wonder for the power of technology – the abundance of pixels. Furthermore, as far back as the Egyptians and Greeks, the body was depicted in its idealized form, and further, as a metaphor for the ideal. Corporal faults were minimized, even in specific representations. I am interested in the strong sense of self-identification that all viewers experience when viewing depictions of the body. Rather than a simple pleasure, though, I seek discomfort and heightened awareness, which is a more complicated kind of pleasure. I aspire to make work that encourages an acceptance of discomfort and a curiosity for strangeness.

Sabin Bors: There are numerous references to ambivalences of the body, Laura, and the cosmetic relation to our own bodies. Digital and virtual representation have impacted culture and led to new enquiries around the role of the body in (making) culture. Textiles contain in their fabric signifying memories and profoundly affective states. How do you see the relation between the material meaning in textiles and embodied knowledge and affect?

Laura Splan: I am particularly interested in the cultural baggage of craft materials and processes – how not only the form and function of an object can imbue meaning, knowledge, and affect, but also the materials and process by which it was made. And I often think of myself more as a character in a fictional narrative when making my work perhaps because the bodily experience of producing it can be so peculiar.

In Prozac, Thorazine, Zoloft, I was as interested in the mind-numbing process of latch-hook craft as I was in the tradition of representation of idealized imagery from domesticity and nature. In Trousseau and its accompanying facial peel sculptures, I was as interested in the ability of the peel material to evoke the fragility of the body in the biological sense as well as culturally constructed notions of fragility as they relate to femininity. Furthermore, the choice to alternate among and even conflate hand-made and machine-made is in an effort to not only question the value of that which is made but also to contrast the experiences of making them – the labour of the body in rendering the body, the obsolence of the body replaced by the machine. Both of these projects are examples of materials-driven/process-driven artworks in which the textiles were primary. I was drawn to them for their potential to interrogate and evoke the entangled relationship between our body and the world around us.

Sabin Bors: It is said that fashion, design and the industrial culture are often more receptive and influential than art as testbeds for aesthetics and its evolution. While various media transformations throughout history have directly impacted the development of artistic research, researchers like Domenico Quaranta say video games are more than just another medium of expression: they not only construct worlds and create stories but generate new collective legends and icons which permeate the iconographic repertories of artists. How does this iconography reflect society and art history?

Claudia Hart: If you are talking about video games generally, I would say that they reflect the times just like all mass media does, whether television, mass-market cinema, advertising, or other commercial products like clothing or the other products of the entertainment/consumer culture. This is the basic “visual studies” premise; we study them like anthropologists have always studied cultural artifacts. Frankly, I find game space to be claustrophobic. The only games I appreciate are discovery games without purpose, where one can wander around an imaginary world. Functionally, game interfaces are liminal spaces, halfway between the real and the virtual. “Liminal” is in fact an anthropological term, invented to describe the space of mythological enactment. So as a liminal gateway, a game interface is mythological, not just in the terms I described above, as a cultural artifact, but also as a liminal portal. I must confess, games per se bore me. The choices presented in them are too limited. I’m very ADD, I can’t focus on them. I’m not a fan (let me re-iterate – smiley)

Sabin Bors: In what way have participative media changed over the past decade, Christopher, and how do you perceive its current impact on society?

Christopher Baker: By increasing in temporal speed and extending its physical reach, it entices us with the promise of bringing our physical and metaphysical experiences into parity. This has a significant effect on the way that we imagine ourselves. Clearly this new tool for connecting to others can result in significant and important real-world outcomes – in particular movements, revolutions and action on the ground. But I think as we imagine ourselves as increasingly anonymous in the vast sea of the internet, we begin viewing others in the same way. As we feel our online identities increasingly disassociated with physical identities, we assume the same to others, resulting in some pretty inhumane behaviour online.

Sabin Bors: What about its future? How do you see it evolving in the next decade or two?

Christopher Baker: My personal hope is that we can refocus on the local, the physical, and the relational. I hope that by bringing the physical into sharper focus and celebrating it, rather than replacing it with a virtual, idealized representation, we will become less anonymous and more engaged.

Sabin Bors: I would like to continue the discussion by returning to the question of interfaces and machines. How do interfaces affect the body and how far do you think that the human body has actually become an extension of the machine?

Carla Gannis: I give some credence to the philosophy that the human body is a complex biological machine. We no longer live in a Newtonian universe where reality works like clockwork, so asserting that we are a “kind of machine,” in the age of relativity, need not reduce our “essence” to sheer mechanics and programming. That said, whatever impulses that have driven us to create other, less complex machines (at this moment in history) I think our human-made-digital-machines are still very much extensions of and augmentations for the human body (machine) and its assertion of free will.

Yes, I swiped on a physical book page the other day, I also tried to magnify the text with my thumb and forefinger, but I would not count my adaptation to the iPhone interface as an “extension of the (*singular) Machine” i.e. the Matrix, upon my body. I believe, or perhaps I want to believe, that the relationship is, or in the future will be, more symbiotic, (without getting too close to Kurzweil “Singularity” territory here). Do I believe more complex bio-digital machines may arise that will have profound consequences on my human life and the lives of future humans? Yes. I can foresee a complex consciousness arising in our technologies and a future in which our opinions about ourselves, as the most intelligent life forms on this planet, are put into question. If I am around at this future point, I imagine my “human machine” will be making art about it all. Whether the drive to make art is “magic,” bio-tech, the channeling of a collective conscious, or a combination of all of the above, it is my hope that it extends into the future matter and composition of this planet.

Sabin Bors: But is it possible to talk about a community through the body? What sort of communities do we construct in ‘real’ life and what sort of communities do we construct in the virtual? Are they a mirror of each other?

Carla Gannis: People talk about and create communities through the body. Sports is one example. One might argue that the rules of play, the mental manoeuvring is really the key to the members’ connections, but without the bodies as actors on the field or court, the community cannot manifest as an entity in its purpose. Likewise, online gamers rely on 3D simulated bodies as signifiers for the communities to which they belong, or the ones that they want to join. The need for camaraderie and competition seem to be prime movers in online and offline communities, so I suppose both constructions reflect similar aspects of the human condition and the social body. From certain vantage points the customs of a football player and a World of Warcraft player can look equally strange, absurd or “cool.” And yet, the stakes of body commitment to a real world community are higher, for example when one joins a protest group and is fired on by police. One’s virtual avatar being kicked out of an online community can be demoralizing, but rarely is it life threatening. The parameters of IRL communities are still set by the physical body’s fragility and mortality. URL social constructions can include simulated murder and death where only the encoded body pays the price.

Sabin Bors: What sort of concepts have you developed over the years by handling the different amounts of data and information and in what way did they influence your work as an artist and as a researcher, Victoria?

Victoria Vesna: My work has moved progressively to looking into the nano, biotech, neuroscience realms as well as our relationship to our natural worlds and in particular the animal kingdom. The amount of data is unbelievable and it becomes critical to engage in a way that illuminates how our consciousness is shifting with the social networks. We are moving towards a collective mind with such speed that there is little time to turn around and consider the changes that are happening in our biology and our minds. For the past decade and moving into the next, my main challenge is to create experiential environments in which the audience participates actively and is prompted to stop and move as little as possible.

Sabin Bors: Do you think a digital body can reflect our humanity, Claudia? In what way exactly?

Claudia Hart: A digital body reflects our humanity by not quite ever being able to capture it. Digital bodies are always uncanny and weird. They are both dead and alive and never having the privilege of truly facing death so are never humbled by the fragility of life and therefore never develop the quality of empathy. They lack all the really good stuff. I think that’s how.

Sabin Bors: Does technological vivification of the virtual body alter traditional feminist critique by blurring the possibilities to distinguish what sort of body is it and what is being performed?

Carla Gannis: Sure, it can alter traditional feminist critique, and on some level I think it should. For art to affect change it must be past, present and future aware simultaneously. The necessity for feminist voices in the arts has not slackened at all, however there are new and additional variables that shape gender identity and influence our continued struggle for equity. Based on our expanded access to the collective conscious new problems and solutions present themselves. The virtual body politics of young women who have grown up on line are quite different, and yet still akin to, their sisters from previous decades. I believe traditional feminist critique can coexist and dialog with new, technological perspectives.

Sabin Bors: Skin is autobiographical. How does the virtualization of our experiences affect our personal narratives, and how does technology change our relation to our own bodies?

Cynthia Lin: Skin autobiographically reveals both interior and exterior influences. It forces us to reconcile the inevitability of aging and death as well as the many things beyond our control. Perhaps virtualization allows us to depart from our skin and re-make ourselves as we wish. It might give people a greater sense of control over their destiny. It might be particularly advantageous for those who feel their mind should be valued more than their physical appearance. Or it could erase the notion of self, which is dependent on a body, and replace it with a sense of “collective being” constructed through engineers in dialogue with our collective desires. Another development is the disappearance of chronology. It’s possible to have multiple simultaneous experiences with multiple body parts: to listen to music while reading a screen while absorbing smells and tactile sensations in the physical world. Past and present are equally archived and intertwined in Google searches. Perhaps many lives can be concurrently lived in one body. Mind and body are inextricably bound, though, and the body always wins in the end.

Sabin Bors: What do avatars and recombinant bodies tell us about self, self-reflection and the ‘other’ in online and virtual representations? Does the virtual reverse reality and normative dichotomies or does it continue to reflect the same social and political tendencies as in quotidian experience? How will these issues be reflected in the near future, in your opinion?

Victoria Vesna: Ultimately, the mirror of self in the online world is a manifestation of the unconscious mind. The separation of the avatar one creates from oneself is an illusion and that is what makes it so attractive. There is a general agreement that this is a fantasy world and one can play out ideas, imagery, identities – supposedly without any connection to the self in daily life. But if you take the time to analyze what you are creating, and this is true for all of us, you will find that it is you in a different form. Sometimes what emerges is so troubling and strange that your rational mind will reject the notion that this is a reflection of you, but this is also an opportunity to look into the mirror of your “other.” How this will reflect in the future is dependent on whether we recognize the power of these representations and own them or if we allow others to use them.

Sabin Bors: Victoria, you mentioned in a different interview that when tracking how people play with gender, it is fascinating to notice that most decide to be their opposite or transgendered. Could you please detail on this?

Victoria Vesna: To answer why exactly most people decide to be the opposite or transgendered would require an expertise I do not have. I could only guess that the opposite is a natural way to balance the male and female and the transgendered is a blend that somehow keeps one from determining either. When we launched Bodies Corp almost all created were hermaphrodite so clearly it is a preference when building an avatar. There is definitely something liberating in being without specific gender.

Sabin Bors: How do different cultures consume the same visual content or information?

Joyce Yu-Jean Lee: American pop culture is pervasive globally and is distributed easily through mass media and the Internet. When I spent time in China, it was interesting that Chinese young adults were more familiar with many aspects of American pop culture that I was! Even with the “Great Firewall of China,” young Chinese will find what is trending around the world through creative solutions. The Internet is an incredible development towards ubiquity of visual content, information, and news.

Sabin Bors: Then how does technology transform cultural ways of seeing?

Joyce Yu-Jean Lee: I think the primary effect I want with my work is to extend our patience for looking and focusing on content. In a recent article published by the New York Times, “The Art of Slowing Down in a Museum,” it was reported, “the average visitor spends 15 to 30 seconds in front of a work of art, according to museum researchers.” Even with extremely renowned works like the Mona Lisa at the Louvre, the average glance duration is a mere 15 seconds. Our Internet and screen-based culture enables immediate access to information, and with mobile devices always within a hand’s reach, there is no need to retain or remember any information after we look it up. I hope my work will pull viewers in with surprise to sustain a gaze longer than they would normally give to video work, despite using the very technology that has reduced our attention span. Simultaneously, I ask, “what will I pose to the viewer once I have their attention?”

Sabin Bors: Christopher, do you think the need to be heard as tackled in your work is a reflection of an individual state, or is it rather a state we have assimilated by connecting with others? Do people share because they feel an ‘inner’ need to share or do they share because we live in a culture of (apparent) sharing that incites us to mimic the gestures of others?

Christopher Baker: I think the need to be heard (and thereby validated as “human”) is an inherent human trait that comes as a direct result of our metaphysical experience. I think it starts with that internal experience of the limitation of the body. Sometimes simply being heard is the closest we can get to feeling like we’ve transcended our own physical, bodily limitations. Minimally, it’s like a radar ping – a call and response – and very low bandwidth. Maximally, I believe it’s found in relationship – physical proximity, touch -, people acknowledging and protecting each other’s physicality – and, by extension, their meta-physicality.

Sabin Bors: One of the aspects I really liked in your work, Carla, is the idea that an enduring body engages enduring images. Can this renegotiate the statute of the image as such?

Carla Gannis: I am going to begin by being very literal about the enduring body. I had just finished a feat of endurance prior to making this work. I successfully ran 26.2 miles during the NY Marathon. I put my physical body to the test during 7 months of training, and will admit I was surprised to find that finishing the marathon felt as rewarding to me as completing a solo art exhibition. I have always been a physically active person, but enriching my mind, as the source for generating meaningful imagery, has always taken priority. I committed to my body as a vehicle for endurance and achievement in a way I had never really done before. During this period though, I had to come to terms with the limitations of my body. There was no app I could download to augment my speed or capacity to run great distances. When my mind can’t remember something I’ve grown accustomed to searching online, to extending my mental acuity via technology. There was no technology that could run for me. Other than a good pair of running shoes and a Nike app that charted my progress, my body, and without a doubt my very persuasive mind, were in this alone. At any point I could have programmed my virtual avatar to run a distance equivalent to 26.2 miles in virtual space, and she could have done it without Gatorade, and 20 mile training runs and groggy 6 a.m. risings. She could have run the distance in less than 4 hours, and she wouldn’t have ached for weeks after, nor dealt with duelling voices in her head telling her to stop and to keep going. Reflections on my virtual capacities and my physical constraints produced an enduring image for me, and embodied the multiple conflicts that we, as a species, have had for centuries between our real selves and our imagined selves, between a gravity bound body and a seemingly disembodied, soaring mind’s eye. The mind’s eye is now capable of embodying itself as code that compiles as an image, an image that can operate in real time and in an X Y Z space akin to our physical body habitat. What are the implications, upon our bodies, our images and our futures?

Sabin Bors: Joyce, do you think that the contradictions between pictorial spaces within different cultures hold the power to inspire the viewers to perceive space as a ‘virtual’, mental or psycho-geography?

Joyce Yu-Jean Lee: Yes, viewers are beholden to the ideologies embedded in pictorial space. As an artist interested in ethnography, I am guilty as charged! In general, how we interpret a virtual space largely depends on how the artist has constructed it, and the cultural cues they employ to trigger certain reactions or ideas.

Sabin Bors: Data bodies allow us to search for information contained in other bodies, yet it is an exchange that is permanently mediated by the gaze of the computer. Most interactive works are based on image distortions controlled by machine code or scripts. What does this leave us? In what way do we actually interact?

Victoria Vesna: Believe it or not, I still occasionally get messages regarding bodies created twenty years ago. People were and still are very naïve about inputting their data – privacy is long gone. Multiple machines around the planet sharing bits of our minds become an emergent network that is evolving into the artificial intelligence we imagined as human looking robots. In fact, it is the network that takes on a life of its’ own and we live forever with no control of how our data is used, shaped and where it travels. It is something we have to just accept – there is no turning back anymore. Our interactions are tracked and become a pattern that is mapped to other sources and there is little or no control. The only place we have left, and who knows for how long, is the imaginary, the psychic, the irrational.

Sabin Bors: In my opinion, most of the works present us with a ‘post-representational’ subject; instead of being a mere representation of the body, it is endowed with full potential action. The artists create models rather than images and these models are highly dependent on the idea of agency. Do you think such agency could become a politicised premise of the works themselves?

Patricia Miranda: I think the works present both, body as representation, and body endowed with action. Claudia Hart, for example, creates an avatar that, despite having agency over movement, is trapped in a virtual space, banging against the glass of the monitor to get out, to no avail. Vesna’s Bodies Corp 2.0 offers a kind of false agency, where you are able to create an avatar body in the gallery, choosing texture, gender, age etc., yet once you create it the program copyrights your body and you no longer have any rights to it. Chris Baker’s large-scale projection has five hundred selfie videos, which on an individual basis may seem to express a lot of personal agency, as each person made the video and uploaded it for the world to see. Taken as a whole though, it can seem like a sea of indiscriminate narcissism, agency that exists only to reflect back its own self-congratulatory image. It is both celebratory of individual creativity and numbingly undifferentiated. Carla Gannis’ piece The Runaways posits her actual self against her virtual one, juxtaposing the vulnerability of an actual woman running in the outside world and all the dangers that can imply, with her virtual counterpart who has unstoppable energy and capacity within that virtual realm. At times, her avatar appears almost demonic, as she overtakes the real woman and races ahead. So I think the question is more about agency itself, how we define and utilize it as citizens of the world. Certainly, technology offers people more access, more connections, more agency to express themselves. This exhibition perhaps asks – what are we doing with that productive space where agency happens? And how do we reconcile the virtual with our fragile physical self?

Sabin Bors: Could you please comment on the transformations in e-commerce, corporate marketing, and corporate culture over the past decade?

Victoria Vesna: The speed with which the commercial network has expanded is way beyond any expectations or predictions. Indeed, it is the very essence of value that is shifting and our bodies are branded – literally. We are all now part of a collective machine network whether we like it or not and there is a small window of opportunity (quickly becoming a sliver) for artists to participate in the developing new economy, a bit more free from the established gallery system. The fact that our identity has become so deeply connected to commerce is troubling, but it is so entangled already that now it seems we have to surrender to that reality and look ahead. At this point, there is not much we can do other than keep and awareness about what is transpiring and how we are used in this emergent system. We sign agreements without reading, put our creative work or valuable information of any kind in clouds, without thinking, freely giving away our work all to be stored by someone we do not know and in some place that is unknown to us. I am interested to use Bodies Corp as a test case for e-commerce as a conceptual piece and am now working on setting up a business plan for this idea.

Sabin Bors: In the end, I would like to ask you, Cynthia, how do you, as an artist, witk with technology to reveal the conditions of the human body?

Cynthia Lin: I make direct scans by pressing the body onto the glass of the scanner. This starting point evokes associations with surveillance cameras, selfies, webcams, and medical devices such as sonograms and MRI’s. It makes us realize how we are perpetually recorded in numerous ways, inside as well as outside our bodies. Vulnerability is a condition of the physical human body and also a condition of our data. Furthermore, the desire to be seen and to document continues to grow through digital means, and inversely, the opportunities for direct physical interaction diminish. We are producing digital versions of ourselves while perhaps losing touch with our physical selves. Digital documentation seems to justify the existence of our bodies in the real world!

Sabin Bors: And I would like to ask you back, Carla, like you ask in your project presentation – who are we? What are we to become?

Carla Gannis: I think our ancestors first began to ask “who are we?” when they imprinted their hands on cave walls 40,000 years ago. It was an act that simultaneously posited a question and produced a mark of posterity, like saying we don’t know yet, but here we are trying to make sense of these bodies and our consciousness within these physical frameworks. Perhaps I’m projecting, I wasn’t there of course, but I do think for a long time one motivation in intellectual and artistic pursuits has been to continually ask,notnecessarily answer, through some act of creative process, “who are we?” and too, “why are we?” In my own asking, conflicting ideas have emerged about our collective human identity, such as (1) we are an idiot species, acting against our “better programming,” constantly repeating ourselves, albeit with more advanced technologies, all to the end of our own, and quite possibly, our planets’ destruction; (2) we are tiny strings in an infinite quilt endowed with a wondrous life force that provides each of us with a sense of self. It is roiling, productive, destructive, evil, and righteous, but necessary, at this moment in space and time, to maintain an unquantifiable, unknowable, perhaps absurd equilibrium to things; (3) that we are the collective embodiment of the “enfant terrible,” young, callous and impetuous, but gifted with the capacity — through our innate yearnings to learn, grow, and effect change — to eventually find our deeper connection with the Cosmos. When and how this may manifest I cannot predict, but I imagine it might be unrecognizable to humans in our own time.

I have hope, in life, more than in the “we” of humanity. Life, as we know it, may not continue on this planet, humans have done a lot of damage, but life, as in matter will continue, I believe, somewhere and somehow, through our own invention and intervention,or not… My greatest hope is that it will always be imbued with the impulses that bring some life forms together to build and create and question and dream.

The Runaways is a performance video, where I (filmed running in a real landscape) and “I” (my avatar recorded running in a virtual construction of a landscape) converge as operators in an ontological meta narrative. The central question I am posing is “who are we, as 21st Century minds and bodies, existing within the porous frameworks of sublime natural and technological environments?” Emerging from this query is in an absurdist “survival of the fittest” race, where I compete against my virtual self, i.e. my “super self”, a seemingly immortal piece of encoded human representation residing in a highly mutable digital land of Oz. In the realm of the algorithmic mind anything is possible and virtual me can teleport within seconds to an exotic tropical island or to a snowy winter wonderland, but what are the implications of a real woman running down the middle of a rural highway, not yet denatured, on an icy morning, quite possibly imperiling her life? Once digital entertainment value is added, a kaleidoscopic sky and a 3D avatar, thinner and faster than she, do we really care?

Sabin Bors: How does the audience understand and take part in the issues raised by the exhibition? What was the reaction of the audience and how do people perceive the relation between physical body and virtual entities, as outlined in the show?

Patricia Miranda: Audience is an interesting aspect in this exhibition. In my practice, I am committed to bringing sophisticated thought-provoking work to regional art spaces outside the “centers” like New York City where contemporary art is most concentrated. All audiences have the capacity to engage in these discussions at multiple levels if there is access, and art exist everywhere. This is why I run a project space in Port Chester, NY, twenty-four miles from Manhattan where I live (and just north of Pelham). Pelham is very close to NYC, in a small suburban community, and the art center serves the community in varied ways, through classes, exhibitions, and other programming. It is a wonderful place; they continually stretch beyond notions of “regional.” Since nearly everyone in an industrial society is affected by these technologies, the audience is familiar with digital moving image etc., so the work can feel accessible. In mainstream media the idea is largely to entertain, and moving images deliver that well – children (and adults) love the exhibition when they come in. But they may not be as familiar with the ambiguous – and often more challenging – language of fine art. Once engaged, a second look begins to reveal the more complex messages available through the work, and the audience is then part of the discussion. The audience for this exhibition has responded on multiple levels, enjoying the interactive elements and the aesthetics, and asking questions and discussing the ideas presented. Interestingly, I was asked often about my choice of six out of the seven artists being women, which lead to discussions about assumptions around men and technology, and women and the body. In a place like the Pelham Art Center, someone comes in to see the exhibition, or they may have come for another purpose and discover the work as an unplanned part of their visit. These kinds of interactions are integral to my thinking. I am particularly looking forward to the panel discussion on March 19, where the artists can have a discussion in the space surrounded by their work.

A Post-Scriptum: TechNoBody, or The Realisations of Virtuality

Artists have always been among the first to reflect on the culture and technology of their time. In TechNoBody, visitors are presented with multiple psychologies of carnality and technological conditionings: a faulty and almost obsolete body in the work of Cynthia Lin, a ‘virtual’ competition between self and avatar in Carla Gannis’s The Runaways, the inescapable entrapment of the body within the medium in Claudia Hart’s dark kNight, extending neuronal anatomies in the work of Laura Splan, Joyce Yu-Jean Lee’s ‘virtualization’ of space and the participative intimacies in the work of Christopher Baker, or the personalized habitations of the datascape as assembled cyborgs in Victoria Vesna’s work. We are confronted with a very inner ‘second nature’ which challenges perceptive and cultural (in)formation and communication, as these confluent bodies are involved in a transversal dialogue that probes philosophical issues of corporal existence as well as the separateness and likeness of ‘real’ and ‘virtual’ bodies. Meanings and meta-meanings are often created through failed corporal appropriations. As such, these confluent bodies present the viewer with different understandings of the technologically-mediated agency these bodies hold as autonomous ‘characters’ and social beings who could at any time assume a life of their ‘virtual’ own.

In its almost instructional character, the exhibition is successful in revealing how different artistic processes manifest in the age of information technologies. The works do not explore the ‘intelligence’ of technologies in the arts but instead create space for a shared presence of the body in different artistic contexts and an exploration of how imagination and pre-formatted information (co-)operate a doubling of environments. This is most evident in Carla Gannis’s The Runaways, as the competition between the artist and her avatar places them both in different contexts and blurs the line between the ‘real’ and the ‘virtual’ to create a space that is virtually real. In her seminal work Digital Art, Christiane Paul has already stated that our virtual existence suggests the opposite of a unified, individual body, as multiple selves seem to inhabit mediated realities; Sherry Turkle, director of the MIT Initiative on Technology and Self, has described online presence as a multiple, distributed, time-sharing system. [1] However, TechNoBody preserves a strong sense of individuality and physicality, as evidenced in the works of Claudia Hart, Carla Gannis, Laura Splan, or Cynthia Lin; and it is this sense of physicality that might counterbalance and decenter the drive for the ‘digitisation’ of life.

After more than a decade since its first publication, Christiane Paul’s Digital Art continues to reflect some of the most pressing questions and ideas, showing how digital technologies have been most prominent in the decentering of the subject and the constant ‘reproduction’ of the self without body. Paul stresses that relations between virtual and physical existence unveil complex interplays affecting our understanding of both the body and (virtual) identity. [2] To my own surprise, however, the impulse to re-address questions about man-machine symbiosis in order to explore artists’ opinions about technological enhancements and extended bodies [3] has made me ask myself whether this vital question is properly addressed. Carla Gannis’s answer in particular, that human essence cannot be reduced to sheer mechanics and programming, and that we must think of a more symbiotic relationship that could trigger a complex consciousness arising in our technologies to challenge the anthropocentric perspective of man as the most intelligent life form on this planet [read above], epitomizes both the vitality and complexity of the issue. Can one read in this a resilient synthesis of humanist, essentialist, progressist, and ecologist perspectives? As shown by Paul, digital art projects have shown remarkable inclination towards notions of the cyborg, the extended body, and the posthuman, revealing the various extents to which humans have been prosthetic bodies and cyborgs throughout centuries, by constructing ‘machines’ which could manipulate their limbs. At the same time, online environments seem to replicate this by allowing multiple possibilities to remake the body and create digital counterparts “released from the shortcomings and mortal limitations of our physical ‘shells.’” [4] When discussing Victoria Vesna’s Bodies, Inc., where visitors can create their own (cyber)self as expression of an ‘incorporated body’ which gains new significances with the rise of e-commerce and the ways our data-bodies and online behaviours are tracked, Paul notes that in projects such as this, as well as in the now almost obsolete chat rooms or multi-user environments, the exchange is always mediated by the gaze of the computer, in a confrontation of reflections and online representations reminiscent of the motif of the mirror reflection. [5] It may, of course, be argued that issues of virtual identities and disembodiment in relation to the body, objects, and materiality, together with human-machine interaction involving the materiality of the interfaces and their effects on the body, or networked communication as a form of “disembodied intimacy” detached from the realm of the primal senses and allowing for fluid transitions between “different states of materiality,” [6] are characteristic of a culture of acceleration and can therefore be interpreted under specific politics of time. The intrinsically virtual forms of manifestation define technologies of communication and exchange that have shaped human interactions in capitalized democracies. [7]

The body is neither entirely matter, nor entirely thought; its duration, spatialization, and corporal presence is a mirror of time’s continuous movement of differentiation. The endurant and fluctuating image of time reflects in Carla Gannis’s The Runaways as a paradoxical construction: while the work reiterates ideas of human performance and sport ideologies, often associated with heroism and narrative operations that usually posit the figure of the individual hero, duration is also a means to disturb narrative resolutions and consolidated identities. The avatar-self resists the spatialization of time and its cultural measurements to reflect durational aesthetics intermingling temporal distinctions and the concept of presence. The work’s title averts the viewer that any aesthetics of duration is marked by a conflict with phenomenological time to reveal the unleashed and ‘savage’ force underlying relational and inter-subjective considerations: the runaway is an escapee, a drifting character, unstable and off-beat, spirited and impetuous, rampant at times and clearly insistent. As the ‘real’ Carla and her avatar compete along the linear space-time, a strive to reach indivisibility marks how ‘objects’ of thought, analysis, and representation such as the avatar might eventually escape conventions of time, space, body, image, and medium in confluent encounters and environments. [8] Opposed yet deeply congruent with this perspective, Claudia Hart greets the viewer with a prisoner who is in fact a particular prisoner of conscience. On Synchronics connects multiple separated subjects within a single screen as the ‘incarcerated’ bodies unthread narrative integrities by emphasizing their closure and entrapment. Unable to extend or multiply, Hart’s body smashes against the screen to expose its determinations and the body’s organic inability towards decision making, sociality, or responsiveness; vital capacities are foregrounded, the body seems to unconsciously float adrift, hovering in the inescapable tension created between the technophiliac and the technophobic. References to the rapturous imaginary of the gaming industry and corporate technologization meet powerful criticism of misogyny in media imagery. As G. Roger Denson already noted in 2011 in relation to Hart’s work, “We are wise not to mistake Hart’s female subjects as representations of women, real or fictional. In Hart’s pictorial scheme they are automatons – legatees of Donna Haraway’s “feminist cyborgs,” the name Haraway gives to individuals who use technological advancement to channel their life force into objects that propel them beyond conventional gender constructions. In like mind, Hart channels her life force not just into her female automatons, but into the environments they inhabit.” [9] Often referencing a baroque imaginary, Hart’s female biological form is a “counteractive imagery that revitalizes her personal identity as a woman” in face of media’s devaluation of women.

In an era of techno-biopolitics, Cynthia Lin reconfigures the human body through technology but does so by emphasizing how skin preserves corporal faults and thus renders impossible any claim for ontological hygienes or sanitizing taxonomical systems reminiscent of humanist paradigms, intent of preserving the deceptive boundaries between what is natural and what is artefactual. An ‘organic cyborg nature’ of the human is also unveiled in Laura Splan’s work. Her dress form computerized machine embroidery is nothing like the opaque armatures of implants or gadgets usually associated with out physical colonization or the affixation of our material presence in natural environments; instead, the artist reveals light and transparent textures of biotechnological webs and biomaterial generativity that can be threaded in recombinant organic materialities and imageries. Joyce Yu-Jean Lee creates an imaginary reconfiguration of space, culturally constructed perspectives, and the surroundings as a web of symbols, culture, and technology. By dislocating perspectives and pictorial interpretations, Lee also dislocates cultural consciousness and opens space for an anti-geography or counter-topology. In Christopher Baker’s work, we get a strong grip on how participative media have undermined our sense of presence and intimacy by creating delusive media for sharing and communicating. A work of interactive design, Baker’s Hello World! nevertheless shows that as communication technologies continue to expand and seize our attention and deep attention, isolation pushes us into accepting the invasion or disclosure of privacy in order to make ourselves heard by someone – anyone. The excess of media (re)production and exposure reveals the cacophony of subjectivities between the private and the public.

A disembodied collective self seized by the corporate, Victoria Vesna’s ‘assemblage’ shows how the upload/download of multiple selves, minds, and personalities into computerized networks in attempts to expand individual intellectual, physical, and emotional attributes comes with the price of privacy and identity loss. It counters ideas of “possessive individualism” (C.B. Macpherson) as owner of oneself and independent from others, which are the basis for capitalist market relations in the individual’s transcendence from material relations. This gesture is highly political. While grounded on informational perspectives, the idea that distributed cognition might replace individual knowledge can be seen as a means to counter ideologies of the liberal humanist subject. In the digital universe, self-sufficiency, uniqueness, or ownership are harder to support – which is also their ‘weakness’ in front of corporate abstraction. By privileging informational patterns over material instantiation, embodiment in the biological might lead one to see it, in N. Katherine Hayles’s words, as “an accident of history rather than an inevitability of life.” [10] This perspective does not only continue theoretical debates on posthumanism, but may surprisingly re-address cultural and social formations resting on the “regime of computation,” thus revealing again that questions posed decades ago continue to surface and answers have not been effectual: while this regime produces an image of the universe as “software running on the ‘universal computer’ we call reality,” [11] it can equally erase ontological boundaries between the virtual and the real.

Technology and humans have evolved in inextricable relations. Deep human-machine symbiosis is reminiscent of Andy Clark’s claim that the human nature may consist precisely in its hospitality to the non-human, [12] and propensities to appropriate or integrate the non-biological into our mental profiles shows an apparently inescapable condition. Artistically – therefore, politically –, the real question is whether art can address or formulate ideas and strategies to inform the directions in which we should enable such profoundly transformative biotechnologies to take shape, instead of simply relying on technology to reconfirm humanist perspectives and artistic practices. Artistic strategies, therefore artistic politics. Donna Haraway’s work in particular continues to influence discussions around the mutations in historical narratives brought by technoscience, revealing the passage from the disjunctive logics in Western thought to conjunctive cultural operations where the scientific and the technological or the natural and the artefactual are to be considered ‘organically.’ [13] The important question, in my opinion, is how to address technological corporatism and the corporate embedment of organisms so as to avoid the transformation of mutated time-space-body regimes into apparatuses of corporate technological-biopower. While the bodies in TechNoBody are seen in their close relation to the corporatization of media, mediums, commerce, science, culture – and art, it may be argued that its perspective is still rooted in forms of technoscientific humanism and must therefore only expand to address the issues further. Whether one privileges Donna Haraway’s perspective of a New World Order, Inc., where biology and technology or humans and non-humans swamp in generative matrixes of technoscience as a discontinuous mutation in history that collapses all distinctions between humans as the subjects and nature as the object of knowledge to thus refashion identities beyond divisional hierarchies; or Bruno Latour’s anthropology of science, which is based on continuities between the pre-, post-, and anti-modernities that disregard dualisms and locate the roots of our hybrid thinking in an amodern hinterland – the question is not only if we should preserve species integrity or connect with non-human others as a form of constitutive outsideness of humanity, but, more importantly, if we can avoid the corporatization of these confluent processes. Unmastered immersions into simulated forms of existence can indeed confuse the real and/for the virtual in concurrent technoscientific processes and practices that would ultimately lead to dehumanization, yet the real questions arise – as partly shown in Victoria Vesna’s work – when corporatist and merchant biotechnicians hold the power to transfer simulacra into actuality and thus feed the blind with the biotechnological utopias of ‘perfecting’ the human species. Should we, as Eduardo Kac so suggestively notes, look inside ourselves and come to terms with our own ‘monstrosity’ and our own transgenic condition before deciding that all transgenics are ‘monstrous’? [14] Technologization is inseparable from ways of primitivization: free access (itself an ideological stand) to technological implants and prosthetics entails pollutions, cross-breedings, contaminations and transgressions that might eventually lead less to hybridization and more to forms of (self-)cannibalization.

TechNoBody did not address the eschatological narratives of biotechnological chronotopes, nor the possibilities of counter-human species arising at the confluence of synthetic biologies or genomic enginnering. The exhibition did not address the cultural regenesis of humanity, but instead focused on individual digital regeneses through regenerated forms of perceiving, understanding, and accepting both oneself as such and technological determinations. In the realm of utopian realities and non-utopian virtuality, it is the numerous faults and impotences of the body that might provide us first with an emotional maturity, then with the political courage to embrace our fearful, weak, and ‘monstruous’ self. While TechNoBody does not look at extravagant longings for immortality, for the transfiguration and ultimate perfection of the body – it focuses on digital narratives of belonging and self-reflexivity; it does not look at objectual incorporations but instead reveals the subjective concorporations within the finite cognitive and corporeal limits. It would have certainly been interesting to see artistic approaches depicting how immersion into networks of non-human relations that are animal, vegetal, or viral creates contaminated cross-linkages and inter-connects varieties of human and non-human others. Yet TechNoBody successfully achieves to investigate versions of current identities that take advantage of the subjective complexities of the body in relation to digital technology.

This post-scriptum has been inspired by Arthur Kroker’s claim that the nature of posthumanism lies in the gap created by the contradictions and paradoxes of what he calls the “realisation of virtuality.” While technological drives seem to reflect the reconstruction of the life-world that has created them, Kroker underlines that the ‘digitisation’ of life is countered in popular culture by “a counterbalancing fascination with images of the abject, the uncanny” and “an increasing focus in mass media, with the spectral zombies, clones, avatars, and aliens.” For Kroker, “the essence of the posthuman axiomatic in the fact that technology now eagerly seeks out that which was previously marginalised as simultaneously ways of mobilising itself as it effectively recodes every aspect of the social and non-social existence and ways of drawing attention to technological seduction.” [15] The implications reflect how data and the organic might dislocate within their liminalities, raising numerous questions. Is it possible to see in the monstruous, grotesque, and uncanny imaginaries a reflection of how society actually de-legitimates technology and its associate network of symbolic, economic, and political power? Is it possible to subvert it by misapplying the regime of the code onto the uneasy discourse of the body? Are we destined to float adrift cultural histories and ritually (re)sample (our own) errors in a “digital cosmology” where unpredictable and creative disturbances will unsettle previous orders and reload history? To answer this latter question, we would first have to re-evaluate the ideological constructions that shelter the constituent fantasies of entertainment, gaming, and advertising industries, since they are the first to inform personal lifestyles, identities, and social practices. But will our avatars become defiant automatons who will eventually break free of their conditionings and the simulated sacrificial sanctuary of the screen? Can we consciously instruct male-coded machines on the intimacies, vulnerabilities, and fears that make for the very nature of the human to challenge our cultural heritages? Can we actually escape anthropomorphic paradigms by forming ‘unnatural’ alliances that will enable us to avoid dystopian catastrophes? Why is it that we debate the posthuman but ask less about a possible post-technological? And can we actually master the fetish and hope that the future aegis of fantastical digital realms might teach us all to become minor in ethical and ecological histories?