Virtually Real. Conversations On TechNoBody – Part I

Virtually Real. Conversations On TechNoBody – Part I

On January 23, 2015, TechNoBody opened at Pelham Art Center in New York, a group exhibition exploring “the mediated world’s impact on and relationship to the physical body in an increasingly virtual world.” Presenting works by seven artists working with a variety of media, TechNoBody investigates the perceptions and experiences of the body but also the immixture of technological and scientific concepts in the language of art. From Claudia Hart’s critique of digital technology and the misogyny of gaming and special effects media to Carla Gannis’s performance video where the artist competes with her virtual self; from Cynthia Lin’s monumental drawings detailing minuscule portions of skin to Laura Splan’s mixture of scientific and domestic in molecular garments and Joyce Yu-Jean Lee’s challenge of conventional viewing perspectives; from Christopher Baker’s examination on participative media to Victoria Vesna’s collaborative project on social networking, identity ownership and the idea of a “virtual body” – the show guides the viewer through an array of captivating approaches that challenge not only current media ideologies but also conceptual paradigms underlying today’s digital art, the question of disembodiment and post-humanism in particular.

In this interview with curator Patricia Miranda and artists Claudia Hart, Carla Gannis, Victoria Vesna, Laura Splan, Cynthia Lin, Joyce Yu-Jean Lee, and Christopher Baker, my aim was to highlight the different perspectives on technology and the body as seen by the artists themselves in their work. In the first part of the interview, curator Patricia Miranda explains the curious nomenclature of the show and her choice of works to be presented; the artists themselves discuss the title of the exhibition in relation to their work, the works of other artists in the show and their views on the idea of virtuality; and conceptual discussions are carried around the idea of skin, culturally constructed meanings, pictorial spaces, virtual environments, the aesthetics of navigation, or corporate mannerisms. The second part of the interview further investigates gaming technologies and iconography, corporal faults, embodied knowledge, participative media, human-machine relations, cyber feminism, virtual communities, corporate marketing, avatars and data bodies, to conclude with a post-scriptum to the discussions titled TechNoBody, or The Realisations of Virtuality.

Sabin Bors: Patricia, I would start by asking you to please explain the title of the exhibition.

Patricia Miranda: The title TechNoBody evolved during the process of developing a thesis for this exhibition. Last spring I curated an exhibition called STEAM: Art, Science and Technology (The acronym STEAM is based around the initiatives in the United States for the core curricula in education, which focuses on the STEM subjects of science, technology, engineering and math, and the movement to include art to make it STEAM). The exhibition featured thirty-one artists including two collaborative teams, whose work ranged from artists interrogating the aspirational and dystopian ideas around new technologies, artists exploring environmental challenges and solutions related to the use of technology, to artists employing technology as a poetic tool, like paint or plaster. Some distinct themes arose for me during that exhibition. As I considered contemporary notions around technology in relation to my curatorial work as well as my own art practice, I was struck by how technology always seemed to refer to “new” technology, i.e. computers, video etc. I wanted to expand this notion. Another was how technology has historically changed the way our physical bodies interface with the world around us, mediating, often creating distance between our bodies and the world around us, making us seem separate from nature. Technology has utopian and aspirational tendencies, for good and for ill ends, and seems to answer our desire for transcendence from the physical, freedom from the body, a new fountain of youth, the imperfect self uploaded to faultless machine. It extends our physical bodies beyond the skin, connecting us to information and people in ways previously impossible, while opening doors for the dystopian world of surveillance and corporate appropriation of our most private desires. And despite technology, in truth we still exist in bodies, bodies that age, wrinkle, sustain injury and illness, and eventually die, bodies that reveal our cultural circumstance of place, race, gender, and privilege. The fragile real maintains a hold; the digital still presents in the physical. Our bodies are still ephemeral. And, despite its promise of the eternal life, technology is also ephemeral. We become beholden to its constant updating, planned obsolescence, and redundancy as new products come rushing down the line.

So when Lynn Honeysett, Executive Director at Pelham Art Center, approached me to curate an exhibition considering technology, I decided to explore ideas around bodies and technology in a more succinct and focused way. The title came out of this thinking – the yearning to transcend the body through technology, to be “post” body, and the utopian and dystopian implications of these ideas carried to their fruition.

Sabin Bors: Why did you chose these artists in particular and how do you see their works relating to one another?

Patricia Miranda: Today we are all enmeshed with our technology in a kind of love/hate/desire/fascination. Through our constant tech access, our fascination with our own and other peoples’ bodies is given a strange power that has both connective and subversive implications. These artists each explore how technology affects how we view and interface with the physical body, both actual and theoretical. They investigate how technology reflects our hopes, aspirations and anxieties around bodies, as well as how public and corporate culture constrains, controls, and profits from these notions. They range in technique and material, from hi-tech to low, from digital to the most analog of all media, paper and graphite. This mixing of materialities was essential, creating a dialogue beyond common siloing of discipline and segregation of media, a conversation that straddles media and genre as well as history. Ten works connect contemporary ideas with a continuum of human thought, not presenting the latest trend as devoid of a larger history beyond new media.

Technology has always transformed our lives and changed our relationship to our bodies and the world around us, from the cave paintings of forty thousand years ago, to the printing press, to photography and into the new media forms of today. Humanity has always wrestled with the positive and negative consequences of developing technologies.

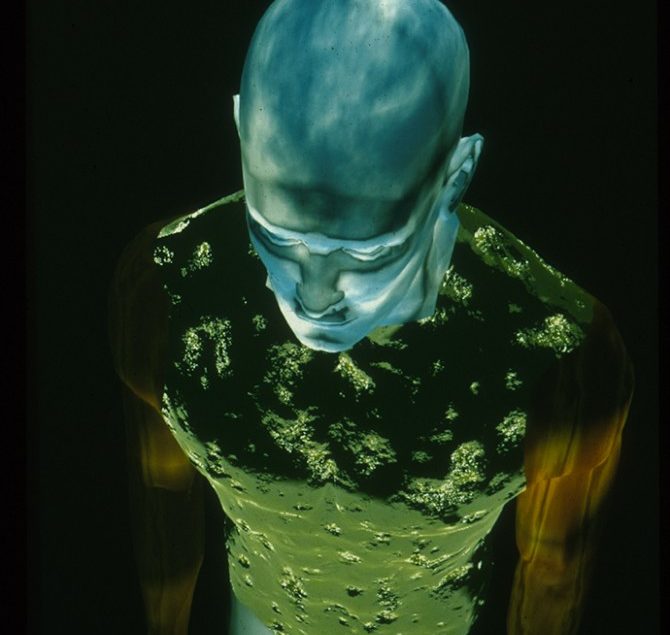

Links are created on multiple levels, by placing Cynthia Lin’s monumental graphite drawing on paper, Crop2YCsidemouth41407, an exploded view of a tiny section of skin, next to the large projected avatar bodies in Victoria Vesna’s Bodies Corp 2.0, and near Joyce Yu-Jean Lee’s floor projection, First Light, where she crawls out of a virtual hole in the floor. Old or new technology, the works all examine bodies, from Lin’s microscopic examination of skin, to Carla Gannis running a race with her avatar in The Runanways video, to Laura Splan’s Negligee, Serotonin, which is made from cosmetic facial peel. She covers her body, peels it off and embroiders it into a feminine garment distinctly associated with the private and culturally female realm. This is juxtaposed with Claudia Hart’s Dark kNight, which uses gaming industry’s “rag doll” technology to create an avatar attempting to escape her simulated reality, banging on the screen in an act of futile agency. Hart often coopts gaming software in a feminist counter to the attitude towards women’s bodies in that industry. All these works open a discourse on our relationship with mediated bodies from a cultural and a personal perspective, across time and genre.

Sabin Bors: Some of the issues raised by the exhibition have been formulated more than twenty years ago, especially when considering the work of Victoria Vesna. How has the cultural and the artistic context been informed by these issues throughout these two decades? What do they tell us about the nineties and what do they tell us about today?

Patricia Miranda: Vesna’s work Bodies Corp 2.0 is an evolution of a project started in 1996 – a prescient representation of today’s corporate control within the virtual. She grasped even then how easily we would hand over our agency in the virtual realm. The work uses humour to communicate a serious subtext, employing new age tropes about textures, and exuberant and fun projected bodies made by the gallery community, along with an elaborate printed analog “contract” that mirrors the digital permissions we sign daily yet never read. This work aptly talks about both the early utopian ideals of the internet, its potential for radical action and connection, the eventual nearly seamless commercial takeover of those ideals, and our willing compliance in the name of convenience, access, and a proscribed agency.

Sabin Bors: I would first like to ask you the same question, Victoria: given that Bodies INCorporated is a work that dates back to 1996, how do you see your work in the context of the nineties and in the context of today? Is there a shift in our understanding of the virtual, its possibilities and its impact on our corporal experiences?

Victoria Vesna: One of the reasons I decided to revisit this piece is because I see that what I envisioned as a semi-dark vision has actually come true – our information has been truly incorporated and it has a major impact on our physical life and this happened so quickly and easily because of the very perception that this is somehow separate from our physical, material existence. Deletion of our data is impossible as was illustrated with “Necropolis” and the endless loop of legalese that we mindlessly agree to is the “Limbo” we get stuck in if we do not follow the rules and regulations. And, finally, there is the “Showplace” where we agree to be used by the corporate machine since we are eager to show our existence… The new beta version Bodies Corp turns to the one realm that we still have to ourselves – our intuition, the psychic, the irrational. The service offered is to copyright the third eye.

Sabin Bors: How do you understand the title of the exhibition in relation to your work and how does your work reflect the issues posed by the exhibition?

Victoria Vesna: The title of the show takes me back to a time when I was very focused on the idea of the body and communication technologies and extended identities. I had a number of works that addressed this issue from 1995-2000 including Virtual Concrete (1995), Datamining Bodies (1999) and Building a Community of People with No Time (2001). For this show, I decided to revive and redo Bodies INCorporated (1996) and consider how things have changed and it seems that the dystopian vision of the project has materialized. The title TechNoBodies in a way summarizes the work I engaged at this time – from bodies of information to communities of people with no time.

Claudia Hart: I think the title reflects a few things. First, technological art is often disembodied, sometimes mediated imagery that is artificial, computer-generated, and sometimes autonomous machines that appear to have agency, as living bodies do. Or it’s disseminated on the web – a parallel universe “inside the computer” with its strangely tangential relationship to the real. The web is virtual and somehow real but also somehow quite real. After all, we spend a lot of time in there on social media, hanging out with folks all over the world, and these are psychically real experiences. Like with you, Sabin. I’ve known you for several years now and have a feeling about who you are and how you live, but I’ve never clapped eyes on you. And although I know MY eyes are real, I can’t really be so sure about YOU. In other words, the relationship between the technological landscape and the body reflects the uncanny collapse of opposites and is both real and unreal as well as living universe and inanimate machine.

The title of Patricia’s exhibition suggests a kind of paradox through the word play she uses, a technological body as not-a-body, and also, a nobody: seeming to beg questions about whether a technological body is different from a real one, and if ANYBODY should even care about that.

Carla Gannis: “TechNoBody investigates the perceptions and experiences of the body in the technological world, engaging scientific concepts in the ambiguous language of art.” The title of the exhibition plays on techno culture and the body’s situation seemingly outside of it, our “disembodiment” in the virtual domain. The “no body” is the simulated body in regards to the work that I have included in the exhibition – a 3D avatar that represents me, in a running competition with me, myself, a real body, tethered to physical space. Is my real body the essential “me” or perhaps just a bio-container, soon to be outmoded?

“[…] for in all creation, in science and in art, and in the fields like mine where science and art meet and blend, in the creating of chimeras of pseudodata, interior worlds of fantasy and disinformation, there is a real making new […] We connect with powers beyond our own fractional consciousness to the rest of the living being we all make up together […] Every mother shapes clay into Caesar or Madame Curie or Jack the Ripper, unknowing, in blind hope. But every artist creates with open eyes what she sees in her dream.” – Marge Piercy, from He, She, and It (1991)

Represented in cyberspace, my technobody is merely a conglomeration of 1’s & 0’s, but as a 3D rendering, it, she, has capabilities far beyond the limitations of the flesh and blood Carla Gannis. Cyber Carla may be a noBody, but she can also be anyBody, any body type, shape, gender, or age. And just as easily, she can exist, disembodied as a #hashtag, data point, or keyword.

Joyce Yu-Jean Lee: My two works in the show, First Light and Invisible Walls, both illustrate figures in a space constructed of pixels. These figures lack a corporeal presence and relate to the theme, TechNoBody. They are trapped and limited to the boundaries of the digital frame, which seamlessly occupies the architectural surfaces – the tile floor and window casing, without any visual disruption. As frameless moving images, these works are immaterial, lacking any physicality other than a thin veil of illumination that brings life to the figures.

Laura Splan: TechNoBody was a title I easily related to when Patricia Miranda approached me about her exhibit at the Pelham Art Center. It conveys variegated meaning in its peculiar spelling “Tech”, “No”, “Body” that I liked the implications of in relation to my work. Tech-No-Body evokes tropes and narratives that I am drawn to such as biotechnology, cyborgs, the technologization of medicine, erasure of the corporeal in an increasingly virtual world, and replacement of the body’s once unique abilities with technological devices. These scenarios can allude to its benefits (i.e. prosthetics) as well as its pitfalls (dehumanization).

Cynthia Lin: I like the “No” inserted between Tech and Body. Does Technology make us all Nobody? Or does it take away our sense of the Body (no body)? Or is Technology emulating the Body, or creating a new kind of (techno)body? My work considers some aspect of each of those possibilities. The fragments of subjects in my work seem anonymous (nobody). The hyper-focused view results in a disembodiment (no body). And our understanding of our bodies is highly dependent on digital experience — for information, documentation, and entertainment. Perhaps the Technobody is the new notion of what a body is.

Christopher Baker: I believe that our attraction to almost all technologies – particularly communication technologies – is fundamentally based on our desire to transcend perceived limitations of our physical bodies. In our day-to-day experience, we feel limited by our “position” in time and we feel limited by our “position” in space. We can’t go back in time or into the future and we can’t occupy multiple physical locations at once. By contrast, our metaphysical experience is virtually unbounded. We can remember the past, imagine the future, dream, plan and hope. This metaphysical identity – which most believe to be uniquely human experience – stands in sharp contrast to our comparatively constrained physical identity, causing us to seek ways – often via technology – to bring the metaphysical and physical experiences into parity. At its core, I believe this exhibition is examining how technology mediates (and sometimes underlines) that physical/metaphysical disparity. Hello World! or: How I Learned to Stop Listening and Love the Noise is a meditation on the uniquely human experience of placing hope in technology as a way to minimize this disparity, while simultaneously bringing that disparity into even sharper focus as we experience the shortcomings of technology.

Sabin Bors: How do you see your work relating to the other works in the show and how do you understand the idea of the virtual or virtuality?

Cynthia Lin: The traditional materials, pencil and charcoal, certainly distinguish my work and contrast it with other works that lack the human hand. I select source material that was made in minutes (a direct scan of a face pressed onto the glass) and slow down the process of drawing into weeks of prolonged meditative observation. I transform a fleeting digital image into time and tactility. My work serves as a counterpoint and physical manifestation that contrasts many of the other works. The one exception is Laura Splan’s work, which also shares a quality of fragility. I think of virtuality as having the attributes of something without actually having a physical form. Much virtual technology is designed to expand or explore an experience desired in real life. In this sense, my work plays with the virtual. The hyper-real scan is a form of virtual reality that enables an exceptional view of pores and skin. It enables us to intimately scrutinize a body because there is no actual body. It creates a sense of intimacy or indulges in desires without consequences.

Laura Splan: Patricia selected Negligee (Serotonin) for the exhibit. This sculpture is part of a larger series I began in 2003 using remnant cosmetic facial peel as fabric. The negligee-styled sculpture is embellished with the molecular structure of the neurotransmitter Serotonin as a repeated decorative motif. The embroidered molecular form is sewn with a digital embroidery process. The precision of the computerized machine embroidery is at odds with the organic and fragile peel material on which it is sewn. The remnant peel results from an over the counter beauty product that is applied as a gel to my body from the neck down. When dry, I peel the “fabric” off in one large hide. The material, which retains the impression of every pore, hair, and goose bump from my skin, is then used as fabric in the construction of the series of heirloom-like garments such as handkerchiefs, veils, and negligees. A lot of my work interrogates the ways in which we attempt to control the body with science, medicine and technology. And the visceral imagery I employ is a way of exploring the insistence of the corporeal in a world that seems set on its obsolescence, mediation, and invisibility. Here the traditional handicraft of embroidery is replaced with a technological process. Imperfection is replaced by precision. The feminine negligee garment evokes the fraught territories of femininity, identity, and sexuality. I often examine the ways in which we attempt to tame the body. Serotonin, which is involved in the modulation of a variety of neural functions and responses (mood, aggression, sleep, sexuality, appetite, stimulation of vomiting) seemed like a good choice to encourage the viewer to map the complexities of these territories. I’m interested in the mutability of boundaries as they are redefined by biotechnology. At what point is the body “cured” and at what point is it replaced.

My work with computerized embroidery foiled by organic forms is an exploration of the tensions between the biological and the technological that I think many of these artists are examining. There is a shared interrogation of representation of the body as it relates to its disembodiment and even its replacement. This often manifests itself in an exercise of comparisons – the representation of the skin vs. the actual skin. One can see similar comparisons in the work of Carla Gannis, Victoria Vesna and Joyce Yu-Jean Lee (real vs. virtual), Claudia Hart and Christopher Baker (autonomous individual vs. collective digital), and Cynthia Lin (hand-drawn vs. photographic). Our shared exploration of the murkiness of these boundaries is what I think Patricia highlights so well in the curation of this exhibition. Much of my interest in virtuality lies in its failures. In our attempt to understand the virtual, we return to this exercise of comparisons. The failures of virtuality are what both reinforce and redefine the real, the original, the authentic, the human. It is a pursuit defined by otherness, by boundaries and very often by ambivalence towards the possibility of succeeding.

Claudia Hart: I think some of the work deals with the impact of social media on the body: commenting on how we spend so much emotionally invested time in these liminal halfway-real spaces on the Internet. Some of the works construct cyborgs – hybrid machine/organic bodies. Some deal with avatar identity – to me about the creation of artificial or mannered identities for purposes of self-branding in the commercialized space of the Internet. What we ALL reflect on is the impact of a technological, hyper-mediated culture on changing ideas about what it might be to be human in the world today. I understand virtuality as a simulation of the real. A virtual world is a facsimile or a model of the real one. To me, the virtual is a conceptual construction, one that is Platonic in the broadest sense, but is specifically a model of the real that could be a computer generated, or physical or just an imaginary one.

Carla Gannis: We are all reflecting on the various positionalities of the body within the time and space of our existence, whether through simulations, projections, internet scraping, analog drawing, or neurotransmitters interwoven into fashion. I find there are quite a few dynamic conversations that arise between my work and other works in the show. For example, in Lee’s work her virtual self attempts to climb into real space and likewise my virtual avatar converges in “real space” with the videographic representation of me (i.e. a “more real me”), whereas Vesna has created an interface where users can create virtual avatars of themselves in real time, albeit within parameters and with limited agency. Likewise, in Hart’s work a collective virtual body is manifest via collaboration between 24 “human artists” and in Baker’s work 1000s of video diaries are compiled to suggest both our continued human desire for an individual electronic voice, and the flattening influence of technology when all of our voices can be delivered at the same time. We each are examining, along different trajectories, the collapsing boundaries between real and virtual time/space and are attempting to trigger empathetic responses from our viewers to the 21st century human condition. Coursing throughout the works at various degrees I also find dark undertones about the co-optation of the body and self in an increasingly digi-corporatized world — one that seemingly offers “empowerment” to our digital identities, but with the price of its, or should I say, our autonomy. Lin and Splan’s work offer stark counterpoints, through physical objects, to the other electronic investigations of the 21st body politic. Skin, represented at a macro level and as a garment, forces us to more closely examine our attraction and revulsion to the “meat space” we inhabit. The reference to “meat space” in my own work, is less physical, but linked to these artists’ work in my questioning of the flesh and bone body’s fragility and capacity and nature when pitted against a virtual super self.

In trying to understand virtuality, the first adjectives that spring to mind are unreal, intangible, dematerialized, incorporeal, nonphysical and – in the context of this discussion – simulated and computer-generated. As I type this, images from Lawnmower Man, Tron and eXistenZ dance behind my eyes. (smile) Then there are other sensations that arise, and I perceive the techno-virtual as “magical”… in a way. And cosmic. “It” is an ever-expanding “no place” that is empty and full simultaneously; a space when and where the data ghosts of our former selves roam freely; a dimension with infinite possibilities for future self-iterations; a time where age, gender and location mean less than meme, mythos and metonymy. Techno-virtuality can be the outpouring of our dreams, experienced in our single skulls, across a network of linked minds — encoded as representations that a “real” populous can feel and love and hate and believe in. And this virtual realm can be as painful to our physical selves as a slap in the face, as beguiling as a kiss, as enlightening as a hike to a mountain top. Therefore I perceive the virtual as real, even when I described it earlier as unreal. The conundrum. Should there be a day when the big plug in the electronic cloud is pulled, still I believe that the impressions made upon me during electronic immersion will remain. But, of course, we have inhabited the virtual world since our first thoughts as babies, when words and images emerged in our ineffable mindscapes. The emergence of technologized virtuality I see as an effort to address, if not alleviate the alienation of our self-contained virtual domains. I’ll end with a favorite quote from William Gibson’s Mona Lisa Overdrive: “she’d dreamed cyberspace, as though the neon gridlines of the matrix waited for her behind her eyelids.”

Joyce Yu-Jean Lee: I see my work tangentially related to a few works in the show. First Light conflates traditional viewing perspectives by transforming a point on a plane into a void, then into a spotlight, and then back into a point. Presented from a bird’s eye view onto a life-size figure seemingly beneath the surface of the floor, the picture plane morphs between positive and negative space under the viewer’s feet. Similarly, Cynthia Lin’s drawing pushes traditional viewing perspectives with a larger-than-life, close-up gaze of human skin magnified into a treacherous foreign topography. Carla Gannis’s The Runaways illustrates her avatar endlessly navigating a virtual environment, paralleling with my self-portraiture captured via green-screen video. I think of virtuality as exhibiting qualities of the real without actually being real. The virtual can be, and is in the case of TechNoBody, representations of the real by digital or computer mediated techniques. The difference between the virtual versus real is that the virtual does not exist in the exact physical form or manner as the real.

Victoria Vesna: Patricia Miranda did a great job with the works she chose and how they are positioned. It is great to see Chris Baker’s massive video wall at the very entrance – database aesthetics in action. Made me think of Lev Manovich and all the work with selfies that is emerging in all contexts. To the left of this wall, she placed a computer station for people to enter their info and create the body. As you go into the main gallery, you see Laura Splan’s dress that is very much connected to issues I have been interested in for the past decade – the biological body and beyond. I think it was great to put this in the middle of all virtual bodies around – Carla Gannis’s Runaway bodies along with Claudia Hart’s 3D shooter game style bodies – all playing and questioning the aesthetic of avatars online. I have always challenged the separation of virtual and real that relates directly to the separation of the flesh and spirit. In the piece that preceded Bodies INC – Virtual Concrete – I directly address this.

Christopher Baker: Each of the works in the show examines the boundary between our metaphysical and physical experience – or reframed with respect to the mind/body dichotomy -, our internal (mind) vs. external (physical) experiences. For example, Cynthia Lin’s exquisitely detailed drawings of poetic boundary between the inside and outside of the body – the skin – suggest that by zooming in close enough or by understanding that boundary with enough detail, we might be able to pass through its interstices and occupy both internal and external spaces. Yet in that detailed examination, we might also become aware of the beauty of physicality on its own terms, rather than in sad, limited contrast to the “superior” mind. In a similar way, I think that Hello World! demonstrates the futility of attempting to connect with the “outside” via technology – but simultaneously reveals the beauty of our collective attempt to connect with each other and transcend our physical limitations. Ironically, we become connected not through our shared success, but through our shared failure. I find that beautiful.

I tend to be put off by ideas of the virtual and virtual reality – primarily because I’m an advocate of embodied technologies and embodied interactions. Embodied technologies are those that engage our physicality in the present place and time. In my understanding, mind/body distinctions are artificial and inhumane. This view has largely emerged as a product of my religious upbringing, where mind/body were presented as distinctly separate and competing realities, and my work in neuroscience where consciousness is thought to have a physical, neurological basis. The mind is certainly mysterious but I don’t believe it exists without the physical body. Thus, I tend to be attracted to non-virtual technological experiences, or at least experiences that don’t supplant the physical.

Sabin Bors: Skin is a burdened surface; it is the site of social and political investment, body memory and fantasies. Why did you chose the monumental expression of skin in your works, Cynthia?

Cynthia Lin: Such content is inescapable, and that interests me. When humans recognize human skin, they instinctively react with visceral familiarity. The work functions as a Rorschach test — it draws out one’s fears and desires, which can then be examined. An awareness of race, sexuality and gender, or expectations of beauty are brought out. The monumental scale intensifies this confrontation. The drawing aspires to become a space that engulfs the viewer, rather than an object to be looked at.

Sabin Bors: In his reading of one of Freud’s essays, Didier Anzieu shows how the double-layered structure of the ego replicates the skin: as the epidermis protects, the ego is surrounded; as the dermis records stimuli, perception and consciousness register memories. The ego is formed through our first experiences of our skin, and the skin ego takes shape through memory. How would you comment on this and how does the idea of the virtual affect such relations?

Cynthia Lin: I wonder if we are increasingly dependent on our eyes for information, and much less aware of haptic experiences. And I wonder if the unexpected, illogical or enigmatic are less likely to occur in a virtual construction, even as technology improves to include many sensory experiences. Our sense of scale and sense of the physical relatedness of things seems to be changing, as the physical body ceases to be our main point of reference. Gravity or weight as well, and also a distinction between interior/exterior experience. However, this might not be always bad. Fluidity and weightlessness – liberation from the physical constraints of the body might invite new directions for the imagination.

Sabin Bors: Laura, do you think textiles have a privileged relationship to the senses and society compared to other ‘mediums’? Can we translate into the virtual all the ritual, magical, ceremonial, and religious uses that have articulated the meaning of cloth in culture?

Laura Splan: I hesitate to think of any “medium” that we interface with as having a privileged relationship to the senses. Relationships to sensory inputs are far too subjective. When one considers differently abled bodies or trauma for example, that notion of privilege is further undermined by the dramatically different capabilities, sensitivities and embodied knowledge of those bodies.

I think we can indeed translate the culturally constructed meaning and ritual uses of cloth in the virtual. Although the virtual presents a unique epistemology, as history has shown, we will continue to project existing culture onto new technologies while the technologies themselves transform culture. And our understanding and implementation of the virtual is evolving with the improvement of haptics allowing the ability to feel the detail and texture of cloth and even skin one day. The real question is what will these virtual textile/tactile experiences be used for. As history has also shown, invention and innovation are not always clear indicators of implementation. “A perfection of means, and confusion of aims, seems to be our main problem.” – Albert Einstein

Sabin Bors: In what way do the fictitious personalities we’re creating in virtual environments impact our ordinary experiences, Carla?

Carla Gannis: For quite some time, there have been artists, filmmakers and writers who have created fictitious personalities on the canvas, screen or page. I think this tendency is atavistic and, I would venture, therapeutic to those humans who are imbued with a more elastic sense of identity. However, I am curious about the impact of the electronic virtual environment on the shaping of our fictitious personae and upon our experiences as “IRL selves.” There is a different agency involved in the real-time simulation of an alter ego in a fully immersive environment. Films like Second Skin have been produced to investigate the lives of people who spend more time in VR (virtual reality) playing MMOs (Massively Multiplayer Online games) than in RL (real life). In this film, “real” love develops between two avatars who never meet, while another player’s real life is destroyed by his addiction to always being online, whereby his second self become his first.

Relative to my own life, the various alter egos or quasi-fictional avatars I have taken on I’ve found to be empowering agents. Speaking and expressing myself through Sister Gemini, Jezebel Lanley, or Robbi Carni, to name a few, has provided me with a less inhibited and expanded voice for the ordinary, gravity-bound, wage-earning Carla Gannis who resides in “meat space.” However, the Facebook effect, meaning that the URL “you” and IRL you should be aligned, has had an impact on my relationship to the virtual world. It has become a far more ordinary place to me. I rarely teleport or fly in Second Life anymore for example. It could be that the quotidian nature of my physical life is impacting the virtual environments I choose to inhabit, more than the reverse, these days. Just a phase, I hope.

Sabin Bors: In your work, Joyce, you usually present alternative perspectives where space is a premise for conflicting yet convergent encounters and experiences. You bring together culturally different perspectives on the pictorial space. What do the contradictions between these pictorial spaces tell us about each culture in particular?

Joyce Yu-Jean Lee: As a cross-cultural Chinese American, I think culturally rooted notions of pictorial space can reveal deeper philosophies, world views, or biases of specific cultures. For example, Western linear perspective is grounded in geometry and measurement from fixed points – namely one, two, or three vanishing points that exist relative to a designated horizon line. In the axonometric perspective employed in Eastern pictorial space, objects are stacked vertically in the picture plane to indicate receding space, often from an omniscient, distanced view. These depictions represent different concepts of identity and the individual’s position relative to others. I see linear perspective as a mirror of Westerners’ focus on individuality, their emphasis on personal opinions over that of the collective. In contrast, the small scale of multiple figures in large Chinese landscapes stems from a communal perspective over that of the individual. This also extends into the cultural varieties of spirituality and religion. Western religious thought manifests in monotheism where choice to believe or not results in afterlife in heaven or hell. Eastern spirituality tends to be polytheistic and the afterlife is cyclical and based on an individual’s behaviour, rather than personal choice.

Sabin Bors: In the Introduction to Database Aesthetics, I remember you saying that the new conceptual fieldwork for the artist lies in the code of search engines and the aesthetics of navigation. If I may quote you, “These are the places not only to make commentaries and interventions but also to start conceptualizing alternative ways for aesthetic practice and even more for commerce. As new institutions and authorities take shape right in front of our eyes, we must not stand by in passive disbelief, for history possibly could repeat itself, which would leave current and future artistic work on the Internet as marginalized as video art.” How has this evolved over the past decade, in your opinion, conceptually and aesthetically? Do you think artists today make an effective use of databases and archives as ready-made commentaries on our contemporary social and political lives?

Victoria Vesna: It is really hard to tell if artists are able to use databases and archives in a way that does not automatically circle back into the very source. There is so much information that is entangled in various interests, whether corporate or academic, that it is difficult for anyone to think. So the biggest challenge is to simplify, create interfaces that make audiences stop in the midst of the circulation of data. There is no doubt that the attention span is by default shorter and we are forced into this truncated way of working by the law of attraction. In many ways, the strength of collective participation in online worlds in particular is overwhelming the individual will. In my opinion, the most powerful work an artist can engage in now is to create environments where one is able to unplug. This is a radical act in a in a world that is becoming more and more populated with people, information and noise. Posting yet another opinion about politics or social injustice too often gets appropriated and even manipulated so that in the end it just adds to the collective confusion.

Sabin Bors: From a curatorial perspective, do you think that by appealing to sometimes overly ‘polished’ aesthetics, artworks in today’s digital realm hold the power not only to subvert but to redirect capitalist mannerisms such as those underlying corporate bureaucracy and the technocratic mindset?

Patricia Miranda: In my view, aesthetics do matter. Poetics can communicate in a manner that is open rather than didactic, maintaining a strong point of view while leaving space for the viewer to take agency rather than be acted upon, as is often the case in corporate media or more moralizing forms. At its best, art sets the parameters for a viewing experience, while leaving the resulting experience to the viewer. And art is a personal interpretation, an invitation to rummage around in another human’s brain, to see a world through another’s eyes. It requires participation in the act of viewing. Does this subvert, occupy and redirect capitalist mannerisms? That may be a tall order, a responsibility better left to history than an individual artist. Art is a part of a network of actions that contain the possibility of subversion. Artists reflect the culture they exist in, anticipating, critiquing ideas, asking viewers to stop and think, so they certainly amplify or contradict, as well as participate in cultural change. So, especially on an individual level, it’s possible for art to subvert, or perhaps transform, to enact in the way an artist intends or not. It often sets a tone for intellectual discourse that filters into and impacts other forms. We need art to remind us who we are and the implications of our actions and creations. Art can be a conscience or even a rationalizer. At the same time, capitalism is expert at consuming even radical culture; commodifying it and feeding it back to us as product. So it is a complicated picture.